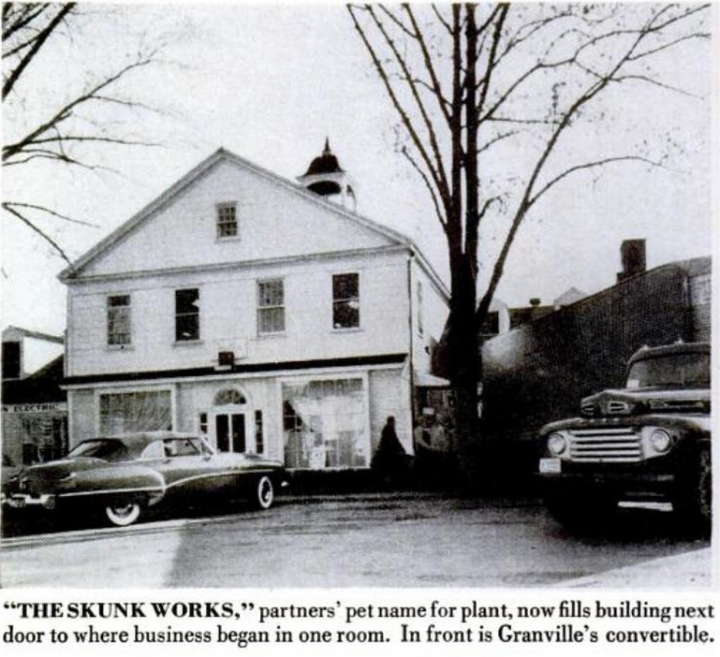

Angelique and Company, Inc. very well may have been America’s first independent microperfumery. The below article entitled “How to Sell a Smell” from Life magazine’s 4th December 1950 issue written by Percy Knauth tells the story of how N. Lee Swartout and Charles Granville began their business on Skunk Lane in Wilton, Connecticut. Affectionately deeming it “The Skunk Works.”

The article also details the ups and downs of the brand’s early years and the various publicity stunts they attempted in order to shift their fragrances. They took perfume marketing to the next level. Swartout and Granville tried to make perfumed snow in the middle of winter and hired a team of starlets to bomb Los Angeles with perfume. Kinda love these guys.

How to Sell a Smell

Percy Knauth, Life Magazine 4th December 1950

One thing that may be in store for all of us in the future is a television set with a smell – a pleasant smell, that is. Bacon and eggs will appear on the screen; the odour of bacon and eggs will waft out at the audience. The heroine of a soap opera will open her arms and purse her lips for a kiss; out to the rapt televiewers will come the odour of her perfume, haunting and sublime.

If television ever becomes so titillating, the odds are heavy that the men behind the smell will be N. Lee Swartout and Charles N. Granville. They are president and treasurer, respectively, of a perfume concern known as Angelique and Company, Inc., and they are known to stop at nothing. Their concept of “the captive audience” is nothing so conservative as chance crowds of people helplessly trapped in a living room or a railway station. These men besiege cities.

In the last four years they have attacked potential customers by spraying perfume wholesale into city streets; they have delivered it in the form of a gigantic Easter egg lowered from a helicopter; they even have attempted to make the heavens release perfumed snow. And in their most dramatic air attack they staged the world’s first perfume bombing of a city by a fleet of airplanes.

The perfume business has always been notoriously and stiffly conservative, waging its commercial warfare with sleek, insinuating advertisements. Yet in this esoteric world of smell-for-sale, the shrill and brassy methods used by Angelique and Company, Inc. have paid off with unprecedented triumph. Starting with literally nothing but a perfectly empty bottle and an almost equally empty idea, Mssrs. Swartout and Granville today own a $1 million business. What is even more notable is that their product seems to have some solid merit. Recently one professional perfumer conceded primly, “Angelique is sensational but sound.”

Both Swartout and Granville are spectacularly unlike the classic concept of a perfumer, who should be a nice blend of the dapper, the exotic and the mysterious. They are both remorseless extroverts and pranksters who go at their trade in the spirit of college boys trying to supplement their weekly allowances. Swartout, 38, is a lean, tall fellow addicted to gadgets like trick neckties that suddenly fly straight up from his shirtfront. Granville, 44, is a puckish character with a pensive bespectacled face, is so restlessly in search of new ways of expressing his personality that he finds it difficult to sit still. Both men naturally rejoiced that, when they launched their perfume venture, they were living on a road called Skunk Lane. Ever since they have called their company “The Skunk Works,” even in public prints.

In January 1946, when Angelique began, the French perfume industry was returning to the American market for the first time in six years. The field was littered with the remains of fly-by-night American companies born of the war years. So any good business counsellor could have told Swartout and Granville that their timing was singularly silly.

But Swartout and Granville were not canny economists. They were commuters – which is really why it all began. Commuting to New York from Wilton, a small and charming Connecticut town, demands about three hours daily on a train; and both Swartout and Granville had been doing it for years. While they were both successful men – Swartout as New York manager for Swindell Brothers, manufacturers of bottles for the cosmetics industry, and Granville as an efficiency engineer – they yearned to live intimately with the rural charms of Wilton which they then enjoyed only with the dulled senses of the commuter. They talked about their yearning often. One day they decided to quit yearning and do something. “Charlie had made a survey of a perfume business,” Swartout recalls. “He noticed that it made a high rate of profit. Also, the work didn’t seem too hard – mostly a matter of selling the stuff. That combination interested me.”

On one of their last evenings on the train as commuters they decided their positions on Angelique’s board of directors by flipping at 50¢ piece. Swartout won the toss and became president. His first official act was instantly to appoint Granville treasurer. By the time the train pulled into Wilton, Granville’s wife had been named vice president and Mrs. Swartout secretary. As working capital, each of the men agreed to put up $4,000.

If either Granville or Swartout had known very much about the business they were entering, they probably would have used the 50¢ piece to buy a few beers and forget the whole thing. The perfume profession is not only tightly organized; it also studiously cultivates an air of mystery. Creation of a new perfume demands an art combining some of the more recondite skills of tea-tasting, musical composition and advanced chemistry. The final standard of quality, aside from the individual reputations of the ingredients used, is determined by the nose. Some of the basic smells, which come in the form of natural or synthetic essential oils, are almost unbearably sweet. Others are so horrible that an incautious whiff can cause acute nausea. But each one has a particular quality which the perfumer knows will give certain notes in the harmony he wishes to create. Once he has assembled and mixed them, he “fixes” them with some such substance as musk to insure that they all evaporate evenly together, rather than at rates according to their varying volatility. “If you didn’t ‘fix’ a perfume,” the men of the trade explain, “you would have a lady smelling differently every few minutes as the various oils evaporated, and some of the smells might not be too pretty.”

In an unguarded moment of conservatism Swartout and Granville decided they would follow the practice of many of their competitors-to-be and would not produce their own scent, but entrust this to an essential-oil company. Their immediate problem was to find a name for their new firm. They hit on it one evening while sitting with their wives and a few friends over after-dinner highballs. Mary Granville, a pert young mother of three, had been brooding about the name for some time. Suddenly she let out a squeal. “I’ve got it!” she cried. “Murphy!”

“What’s that, dear?” her husband inquired.

“The name,” said Mrs. Granville. “It just came to me. I remembered a friend from Hammond, Ind. Angelique Murphy.”

“But darling,” Granville said, “you can’t call a perfume Murphy!”

Mary Granville eyed him steadily and said coldly, “Angelique.”

That ended the discussion.

Next Swartout and Granville set to work on a merchandising plan. Since the scents were made for them elsewhere, their principal task would be to sell perfume. They wanted to build a very “personalized” clientèle. The scheme they devised for this seemed so ingenious that its practicality could have been questioned only a cruel critic or any experienced businessman. They proposed to start out with six different scents, six different names and six different packaging styles. By mixing these up in various combinations, they would be able to assure no less than 1,296 customers absolute exclusivity in a package. Swartout now recalls, “It looked like a stroke of genius.”

Folly and Distraction

In a short while it looked like a stroke of madness. First came days and nights of fretting and wrangling over six names to go with the perfumers which Angelique would sell. While friends badgered them with suggestions such as “Steeple – It Smells to High Heaven,” Swartout and Granville and their faithful wives pored over dictionaries, anthologies, encyclopedias and thesauruses. They emerged with six names: Black Satin, Wanderlust, Folly, Est-Est-Est (this one was an old Italian wine), Distraction and Murmur.

From the firm of van Ameringen-Haebler, Inc., a top house in the manufacture of essential oils and perfume materials, they got six scents. “Then,” says Swartout, “we rushed out onto the road.” Three months later they limped back to their one-room office over the Wilton Electric Shop, lugging their huge suitcases of samples and their huge disillusion. “We just couldn’t take it anymore,” Granville recalls with a shudder. “The more we talked about our wonderful intricate combinations, the more confused we got. We couldn’t keep the different things straight. The mathematics got us down. It developed into the higher forms of algebra. We began to realize that the inventory problem of 1,296 different and exclusive items was colossal. We gave up.”

Salvaged from the grand failure were 1) the name Black Satin and 2) an idea of labelling bottles with the name of the store selling them. Both have proved highly successful. Their schemes now streamlined, it was necessary to decide which one of their six scents they would use. They exploited almost the entire population of Wilton as judges, trying various perfumes out on anyone who would stop long enough to take a deep breath. For a fortnight, Wilton reeked. It also came back for more of one particular scent – a sultry Oriental blend with overtones of luxury. “Luxurious it certainly was,” says Swartout. “It was the most expensive one of all. It cost five times as much as an average perfume, and it had 32 ounces per gallon of essential oils, compared to the average of 26 ounces in a quality perfume.” When they double-checked this perfume against five leading brands in unlabelled bottles and it was still Wilton’s choice, they decided to gamble on it.

Six Strategic Spots

Swartout and Granville had now come up with another scheme to revolutionize the trade, this one a little more rational. “Women,” says Granville, “don’t use perfume nearly enough. Lots of them use it only in the evening for special occasions. There are many who don’t think it proper to wear perfume during the working hours. And most of them think that a couple of dabs behind the ears is all that’s needed anyway.” Angelique, they decided would change all that. “There are six strategic spots where perfume should be applied,” says Granville. “Behind the ears, in the crooks of both elbows and in the crooks of the knees. In these places there is warmth and skin friction, which helps to diffuse the aroma of the perfume. Furthermore,” he adds delicately, “a bit of cotton soaked in perfume and placed in the brassiere is likely to draw favourable attention.”

Angelique’s first order came from a small shop about seven miles away. By August, with their sales force increased to four and the possibility of starting deliveries in October, Granville felt sufficiently courageous to tackle a really big prospect, Saks Fifth Avenue in New York. To his astonishment he got an order. “After that,” he says, “we felt the business was made.”

The Saks sale was no sooner on the books than the whole beautiful bubble burst – almost. One of their new associates, a recently demobilized war veteran named Gordon Hoffman who had been grandly named general sales manager for the Eastern U.S., entered Bonwit Teller’s Philadelphia branch one day and discovered someone had been there the day before, with a perfume called Black Satin. Only it was not Angelique’s product.

The investigation that followed showed not only that there was another such perfume on the market, but also that its manufacturer had copyrighted the name 10 years before. He had only begun to use it recently, however, and this was why it had been overlooked in the copyright search. He was willing to sell the name, though – for $100,000. “There were three things we could,” Granville says. “We could change our name, which meant losing all our investment in packages and labels. Or we could buy the guy out. Or we could go out of business.”

Ignoring the sensible third alternative, they started to negotiate. After six weeks they beat the price down to $22,500, with an agreement to pay $5,000 down, $2,933 every six months for three years. In their elation they had no time to analyse their firm’s financial structure at this point. “All we could think of,” Swartout remembers, “was that we had saved Angelique. It was quite a while before we started asking ourselves what we had saved it for. Not even started, and we were already $22,500 in the hole.”

But they went right on selling. Granville sold his house and car, Swartout increased the mortgage on his house. Both their wives reflectively picked over their jewels. Fortunately, they also sold perfume. By October they started shipping Black Satin to 55 customers, among whom was the U.S. Navy which sold it in ships’ stores. Somewhat later the Army came in too, and Black Satin turned up in post exchanges all over the Far East.

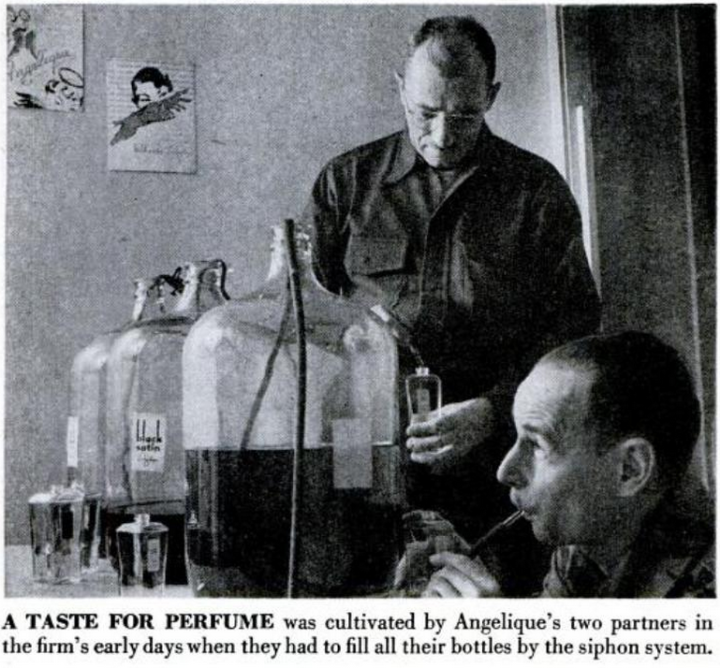

Perhaps the saving stimulant in those times came from the fact that each working day began with a mouthful of Black Satin, taken straight. “We didn’t have any bottling machines,” Swartout recalls with a grin, “so we just siphoned the perfume out of jugs with rubber hoses. That meant taking a healthy suck to get it started. It was strong stuff, but not too bad – 75% alcohol, after all.”

They wound up 1946 with a volume of $27,429 – and a net loss of $8,336. The new year speeded things up: in January 1947 they lost $4,219, in February $2,936, in March $3,931. Angelique’s sales however, had increased in a most encouraging, almost astonishing way. By January 1948 there were 286 accounts on the books and the volume had reached $169,185. A high percentage of this was reorders, which meant that Black Satin had found a lasting favour at least with some. Swartout and Granville had also made some notable strides in their crusade to make the world perfume-conscious. They had adapted an idea used by Lord & Taylor, a New York customer, of spraying perfume into the air. The partners devised portable sprayers which were shipped around all over the country to spray anyone who happened to pass by the stores where they operated.

While this was effective, not to say disconcerting, it really only prepared the way for their first big publicity stunt. “It came to me all in a flash,” Granville says proudly. “One day I read a story about rain-making. Fellow took some dry ice up in an airplane, scattered it into a cloud, and it rained. I thought to myself: why not put perfume in the dry ice? For the first time in history the weather, people’s favourite topic of conversation, would be harnessed for commercial use.” Swartout agreed eagerly: Angelique, at this point, still had very little to lose.

The plan advanced rapidly. A friend in Bridgeport offered to provide the airplane, thereby making Bridgeport the unwitting victim. When the date was set Granville called the newspapers and wire services to cover the advent of “perfumed snow” (it being mid-winter at this time). The response was awesome. “All hell broke loose,” Granville recalls. “The phones were swamped. One New York paper even wanted to cover the stunt with a helicopter!”

Crisis in Connecticut

Citizens of Connecticut responded to the news of the plan with what, at its brightest, could only be called a dim view. There was already nearly a foot of snow on the ground. The mayor of Bridgeport suggested sharply that Swartout and Granville could better serve their state by shouldering shovels. The superintendent of streets said sourly, “I can’t think of anything to say that you could print.” One newspaper reported an assault by a Bridgeport resident upon his wife, whom he struck over the head with a shovel when told him about the Swartout-Granville experiment. In jail, the newspaper said, the man refused to explain his act – “he just breathes kinda heavy.” He had, the paper added, been shovelling his driveway daily for 22 days.

On February 10, 1948, O-day – for “Operation Odoriferous” – dawned, unfortunately, bright and crystal-clear. When Swartout, Granville and their wives arrived to face a sizeable gathering of cameras, microphones and reporters, there was not a cloud to be seen to promise snow. But by the time they had ground up their five pound chunk of dry ice and solemnly poured perfume over it, a few shreds of cirrus clouds had begun to form high in the blue. With glad cries they boarded the airplane and roared away.

The results of the operation, in terms of actual snow-making, are still debated in Bridgeport bars. The pilot, loyal to his passengers, reported “definite” snow flurries “at high altitudes.” Two radio listeners reported some snow – but with no scent. Granville, climbing out of the plane, reported the loss of a $200 wristwatch whipped overboard as he threw out the snow – and promised further experiments in Washington, Chicago and possibly Milwaukee. To this last the reaction was swift. The director of highways of Washington reportedly threatened to sue if one flake of snow fell. From Milwaukee a victim of asthma wrote that she was praying nightly that Swartout and Granville would never appear since she was allergic to perfume, and the idea of a perfumed blizzard was “terribly upsetting.” Finally, in a magnanimous gesture that again made headlines all over the country, Angelique let it be known that further experiments would be postponed indefinitely. “All this,” Granville remembers proudly, “we got for a total of $40.50 – the expense of hiring the plane, buying the dry ice, and the perfume.”

The publicity success was more encouragement than necessary for Granville and Swartout, neither of whom was ever exactly tormented by inhibitions anyway. While their sales rose, t heir minds buzzed with ideas for new ventures. At Easter time they delivered an enormous Black Satin egg to a Syracuse department store by helicopter, while crowds below gaped in wonder. That day the store sold $1,000 worth of Black Satin. An aerial announcement of a new perfume called White Satin was next. This time the plane scattered strips of blotter soaked with the scent all over Wilton. Intoxicated with the heady wine of notoriety and increased sales, Swartout and Granville continued to put money and ideas into their company until at last in June 1948, Angelique showed a profit of $3,430. It was the first time the two partners had used black ink in their ledgers since the company began.

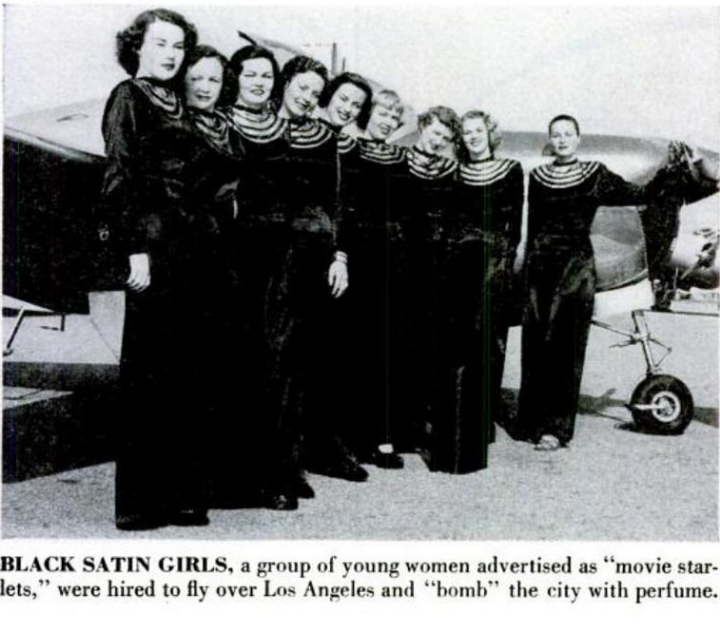

This happy state was celebrated three months later by the perfume bombing of Los Angeles. The memory still brings a gleam to Granville’s eye. This was no piddling, one-plane operation. Twelve Beechcraft Bonanzas were mobilized, each with a crew of pilot and one “bombardierette,” a name fondly coined by Granville to describe the black-satin-clad young starlets who were to drop the bombs. According to publicity releases, the planes were to fly in formation over the heart of the city and, at a given signal from the lead ship, each would release a cloud of perfume. Just to make sure that people knew they were being bombed, Swartout and Granville had planted a few of their portable sprayers around to inject added scent into the atmosphere at ground level.

Details of the raid are still classified information at Angelique headquarters. It was announced that $20,000 worth of perfume was to be used, though the figure was never officially confirmed. The starlets, questioned at the airport, held up bottles to prove they had something. One, pressed by a particularly nosy newsman as to just how she was to drop her bomb, pointed to a nozzlelike opening just above the tail of the plane. “Out of there,” she said brightly.

Luckily, neither she nor the reporter realized the opening designated was for the radio antenna. In any event, the planes took off and shortly after were seen to roar over the city. “It was most spectacular,” says Granville. “Too bad none of the perfume got through the smog. Apparently it just drifted out to sea.”

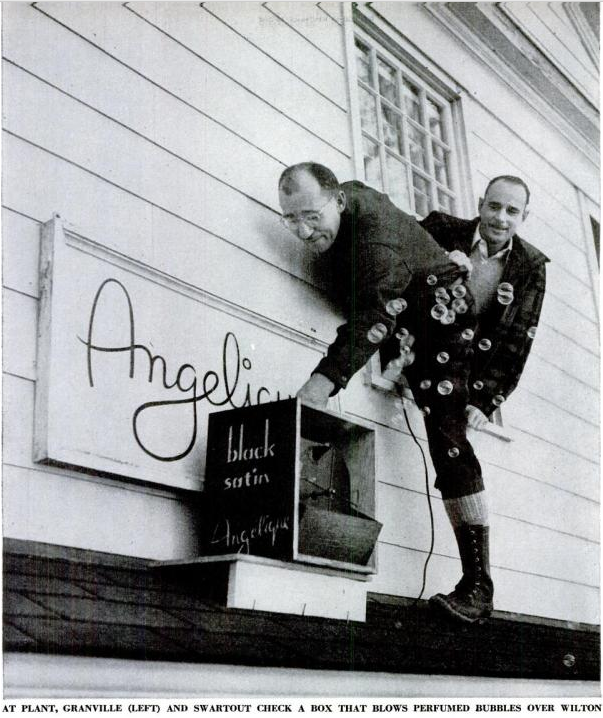

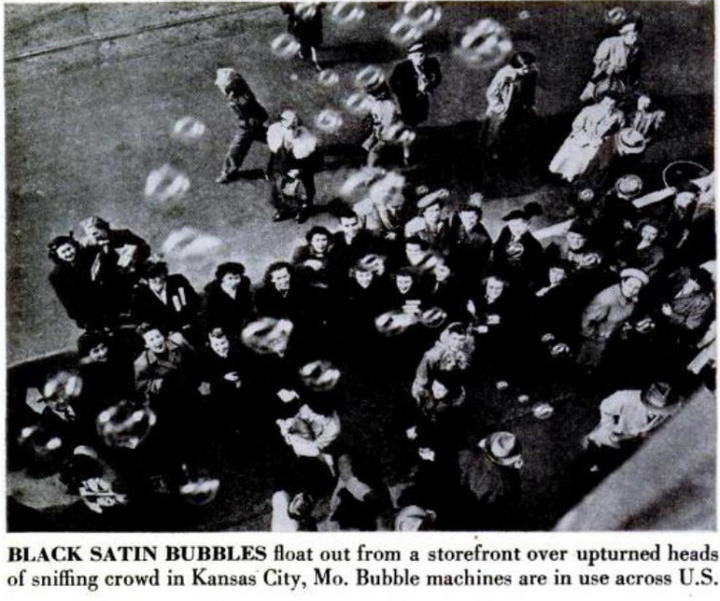

Shortly after this, one of Angelique’s salesmen, Champe Andrews, devised a machine which pumped out perfume bubbles – a successful way of overcoming the inherent lack of motion in perfume advertising. For nearly a year Angelique’s machines blew bubbles all over the country until the inventor of a similar machine who had patented his idea turned up, threatening to sue unless Anglique stopped or paid him royalties. With unusual discretion, Angelique stopped – but recently Swartout and Granville bought two of his machines and got back into the bubble business.

What will come next defies conjecture. Last year Angelique sold $545,649 worth of perfume, cologne, soap, bath powder, pocket-size atomizers, solid perfume and cologne in lipstick form. This year orders have been coming in close to double that rate, and Granville and Swartout find it necessary to devote tedious hours to weeding out accounts because they are getting too many. The Skunk Works have expanded beyond all recognition: a staff of 43 people is busy with bottling, labelling and packaging machines as well as bookkeeping and making coffee for all hands every morning at 11. There are branch offices in New York, Chicago and Pomona, California and one in Canada. Granville has a new house. Swartout has paid off his mortgage. Both have new convertibles.

The sport of money-making, however, must not be allowed to get tame. Granville, particularly, frets about this. Right now he and Swartout are preparing yet another scent to come on the market in February: “Gold Satin, destined to be the world’s most talked-about perfume.” How to get the world to talk more about Gold Satin than any other perfume is the current problem. One immediate way will be to have a big Gold Satin bottle in store windows, above which a small, golden balloon will bounce around, seemingly suspended in open air. “Of course,” says Granville, “actually it will be held up by a jet of air, mixed with perfume, arising from a hole in the bottle. It will look pretty good, and it ought to stop people.”

But the yearning to stop whole cities and make them aware of Angelique persists. Granville has been studying the spectacle of water shortages in U.S. Cities with a speculative eye. “All this artificial rain-making,” he says reflectively. “Now I don’t say we would or could do a thing like contracting to perfume that rain, but just imagine…”

According to Grace at Cleopatra’s Boudoir, Black Satin “was an opulent aldehydic oriental perfume. It would probably be classified as a dry chypre fragrance for women. It was very heavy on the green notes, oakmoss, geranium and citruses. The florals are very muted in this perfume, the perfume reminded me of Ivory soap and Avon’s Skin So Soft. There was a lovely woody sweetness to the base notes, but it still remained sort of musty, I did like that effect though, it reminded me of antique wood, like an old antique carved sandalwood fan that I owned many years ago. There is a sort of what I call the “band aid” scent to the drydown probably from oud, somewhat medicinal with a slight dirty hair smell from the styrax.”

I also came across this short piece from Kiplinger’s Personal Finance’s August 1958 issue:

Checks with lots of scents

Angelique & Co., producer of Black Satin, Red Satin and Pink Satin perfumes, knows how to get its products across. All company checkbooks are dipped in Pink Satin. The dipping costs over $3,800 a year, but it’s worth it. With 48,000 checks issued annually, the company figures each one is handled by 25 people before final clearance. So that means more than 1,000,000 secretaries, clerks, bookkeepers exposed to a whiff of Pink Satin, many of whom write for information on how to buy it in a bottle. Angelique has its checks printed in a rosy pink and decorated with an angel blowing a trumpet. They all read “Pay to the ‘odour’ of…” and so far not a single check has been rejected.

This is just completely fascinating! Perfume bomb over LA? Wow. Really insightful and a great read. Sometimes I really feel you should write a book about the history of Perfume, cuz. You would be the person to do it.

LikeLike

You’re such a sweetheart! Actually, if you are interested in perfume history there is a fantastic book coming out by Lizzie Ostrom (aka Odette Tiolette) called Perfume, a Century of Scents. She runs the fantastic Vintage Scent Sessions, and is just in general a really good egg. I am almost finished with KAI btw. Really into it! Well done!

LikeLike

What a wonderful story! I grew up near Wilton — my father had a similar commute by train to New York — and had no idea about any of this.

LikeLike

Thank you! Their story is wonderful and probably not dissimilar to our current independent microperfumeries out there. Maybe save for having to siphon perfume by mouth, thanks to pipettes!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Serenity Now and commented:

A fantastic story from bgirlrhapsody! I grew up near Wilton and had never heard this particular local history. I do remember, vividly, how most of the fathers and husbands in those towns commuted by train back and forth from Manhattan; many must have longed to escape that commute the way these two did. People think of those towns in that era (the 1950s) as being very stuffy and conformist, and in some ways they were, but they were also populated by large numbers of “advertising men” and other creative people in fields like theater and television. It sounds as if Angelique & Co. was one of the more intriguing examples of local creativity!

LikeLike

Thanks so much for sharing the story! I think these guys could definitely give the contemporary perfume marketing agencies a run for their money!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for visiting my site Cleopatra’s Boudoir. I had read about Angelique’s awesome marketing campaigns before but loved how you put them all together in one post. Very nicely written. Thanks for the shout out too! I have reviewed more of Angelique’s perfumes: White Satin (http://cleopatrasboudoir.blogspot.com/2013/04/white-satin-by-angelique-c1949.html) and Gold Satin (http://cleopatrasboudoir.blogspot.com/2014/11/gold-satin-by-angelique-c1950.html) and will be reviewing Pink Satin soon. Thanks again! Grace

LikeLike

You are so lucky to have been able to smell these! Please share a link with us when you have tested Pink Satin! x

LikeLike

Great story! Norman was my grandfather so I didn’t get to see this part of his life first hand but thank you for sharing this. I sent it with my brother. We have one of the copies of Life magazine that published the article

LikeLike

Their story is really fantastic! Never have I read about more adventurous PR strategies! 😀 I like to think they are a bit of an inspiration to a lot of the small, indie perfume brands making their mark on the perfume industry today. Have you ever had the chance to smell any of their perfumes?? I sometimes see them popping on eBay.

p.s. Lizzie Ostrom also included a chapter on Angelique in her book, Perfume: A Century of Scents.

LikeLike